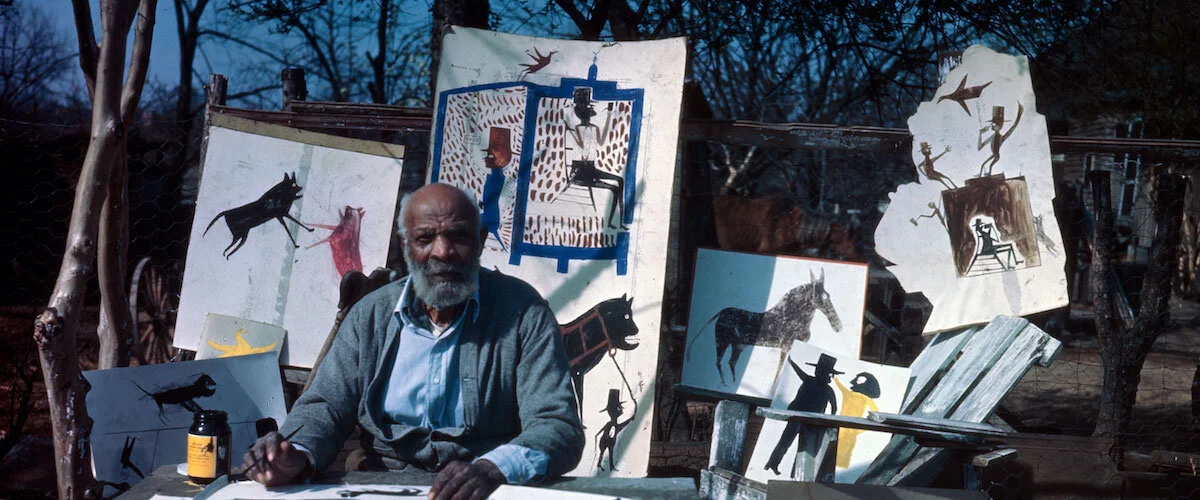

Bill Traylor: Chasing Ghosts

Calling Bill Traylor “the best artist you’ve never heard of” is a bit of forgivable hyperbole. Traylor was born a slave in rural Alabama in 1853 and lived a hard life that Jeffrey Wolf’s documentary sketches in gradually and painfully. In his late 70s, Traylor wound up in Montgomery, Alabama, essentially homeless, and at age 85 started drawing rough figures on scraps of discarded paper, sitting in a chair on the street. It was there, in 1939, that a young white artist named Charles Shannon discovered Traylor and started providing him with poster paints, brushes, and other art supplies.

Shannon both collected and promoted Traylor’s primitive-style sketches — basically blob-bodied people and animals with stick-like legs and, sometimes, crudely sketched objects or buildings. Perhaps more intriguing than Traylor’s style, though, was his subject matter, which stretched back to the Civil War and antebellum South — first-person visions of what by then was distant history to Shannon and his contemporaries. The documentary does a fine job of highlighting this context, pairing the artworks with photos and more-detailed drawings of the scenes depicted.

Whether Bill Traylor: Chasing Ghosts will convince you that the artist was a crucially important talent, however, is an open question. The art experts interviewed are limited to boosters whose enthusiasm overshadows their thin arguments for historic merit. Without question, Traylor had a unique style and vision, but the film declines to put him into the context of other, similar self-taught primitivists, much less to discuss the genre’s status within the complexities and changing trends of art criticism.

It’s notable that Traylor remained a minor curiosity during his life and wasn’t discovered by most art historians, collectors, and curators until the 1980s, by which time Traylor himself had passed into history, and (unmentioned in the film) the cultural standards for artistic talent had undergone a seismic shift.

Rather than comparing Traylor to other visual artists, Wolf opts to pair his drawings with creative works from African-Americans in other media: the writings of Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes, bits of drama and poetry, snippets of tap dancing and jazz. The technique makes the case for the importance of personal expression in any form — a worthy message — but does little to illuminate the film’s actual subject.

Chasing Ghosts is more intriguing as a study of this unlikely artist’s impact on his many progeny. (He fathered between 10 and 20 children by several wives.) The best interviews in the film are with Traylor’s (now elderly) grandchildren and (middle-aged) great-grandchildren. Their views on Traylor and his works are framed by their lives in ways no critic could match. Whatever Traylor’s merit as a artist, his importance to those he left behind is immeasurable and moving.

Grade: B-minus. Not rated, but suitable for anyone older than about 10. Now available via the Grail Moviehouse’s website.

(Photo: Breakaway Films)